What took George Floyd’s mother nearly nine months to bring to the world was taken away in a mere nine minutes.

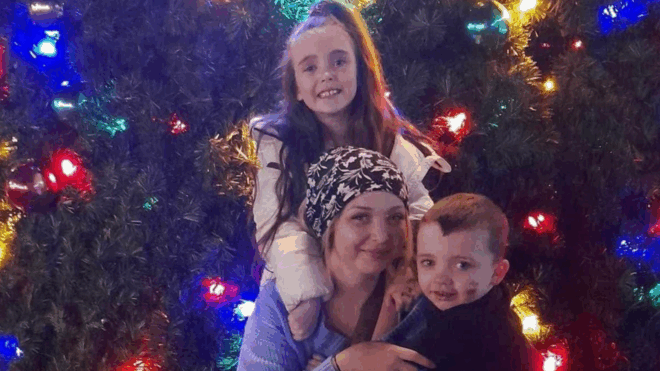

Next month, my son turns 4 years old.

Of course, when he tells me he is “big” now, I grin and I agree. I also explain how he will always be my baby. “Always!” He replies.

There will never be enough justice in the world for a mother who has had to witness her child die, especially by homicide. When I hear the words that I and so many have been waiting for, I feel my belly relax, protruding outward. We have been waiting for the past year and arguably for hundreds of years for verdicts like these. A sigh is released. My chest swells up with my next breath and I exclaim audibly, “YES.”

Guilty. Guilty. Guilty.

I text my son’s father about my joy. My son is mixed race as am I, and while I know he will experience privileges George Floyd never had, I am swiftly reminded of what is also possible for him.

I step into line at the post office of the rural town where I live. I feel myself standing tall and notice my breathing moving easily. In my hand are two letters I am sending to a friend who is currently incarcerated in Minnesota.

In May of 2020, I still lived in Saint Paul, Minnesota. As the fires and sorrow raged on down the street from my house on University Avenue, it was to this friend whom I cried and processed with when Floyd was killed.

Floyd’s murder brought back memories of my time living in the Bay Area when Oscar Grant was murdered at the Fruitvale BART station on New Year's Day in 2009. I am all too familiar with the grief and trauma of losing members of my community to police, so this feeling of relief was one I welcomed. Sadly, it was short-lived.

The man next to me at the post office is a tall man with beautiful long hair. He is what I imagine my son might look like as an adult.

I am handing my letters to the post office associate when this projection of my son says, “I just got out of prison,” as he is asked for a driver’s license and he, of course, does not have one. My belly tightens and I hold my breath a moment too long.

The post-office attendant hands him his obviously important piece of mail anyway.

My breath stays shallow as I note a feeling of fear. Will she get frustrated at the situation and lash out as so many “Karens” do without repercussions? Will they call the police on this man for being “aggressive?” Am I about to experience another traumatizing event involving a Black man and the police?

I am afraid for my baby’s future as a young man of color in this country.

I feel a surge of fear even minutes after the victorious (and it is no doubt a victory) verdict of Derick Chauvin’s guilt because I am quickly reminded of where I am.

This is America.

I am reminded of the rarity of this verdict and of the deeply embedded structures that disproportionately criminalize Black people. And at the same time the criminal justice system makes it rare for representatives of these structures, such as the police, to face judgments similar to people of color committing similar crimes.

I’m not ready to celebrate.

As a Black mother, I exist in the same space as Breonna Taylor’s mother, Tamir Rice’s mother, Duante Wright’s mother — who are among the many mothers who must suffer the consequences of a society that might be inclined to celebrate too early and forget about their lost children.

Every Black death by the police deserves the sort of amplification, scrutiny, and thorough investigative accountability applied to the case against Derek Chauvin.

Only then can we begin to celebrate the future of our children’s safety.