Tiffany Nettleton first noticed something "off" about her daughter's behavior when Haile was just 2. The little girl's temper changed on a dime, and when she became angry, her temper tantrums became extreme. Haile would bang her head against the wall, smear dirty diapers over the furniture and walls, and throw chairs. Still, the photographer and mother of two from Helena, Montana, never dreamed that by age 10, her little girl would be hospitalized for mental illness.

"Haile was extremely violent for being so young," Tiffany recalls. "She just always seemed angry at the world."

She spoke to Haile's pediatrician about it on multiple occasions and was finally referred to a psychiatrist, who diagnosed Haile, then 3, with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and an unspecified mood disorder. (ADHD is the most common mental health disorder diagnosed in preschoolers.) Starting at age 5, Haile began taking stimulants to treat the ADHD. But over the next few years, they only made Tiffany's older daughter more edgy and irritable.

At times, Haile would get so depressed that she'd talk about hating her life or running away. Or she'd become so hyper that "you couldn't slow her down to save her life," says Tiffany. Even more alarming were Haile's episodes of violence, which are common in children with behavior or mood disorders. She would hit, kick, bite, punch, choke, slap, or break things.

"I started to believe that I was either a horrible mother or she honestly did hate me," says Tiffany.

One day, when Haile was 9, she barricaded the door to her bedroom, tried to break her mirror and window, then physically attacked Tiffany once she finally got into the room. When Haile calmed down enough to understand how upset she'd made Tiffany and her younger sister, Eviee, who is 16 months younger, Haile "cried and cried into my lap," remembers Tiffany. "She said, 'I don't mean to hurt you, Mom. It's just when I get mad, I feel like I have to hurt someone."

Tiffany immediately called Haile's psychiatrist and asked for an emergency meeting. Two days later, Haile was admitted into a children's hospital.

Doctors there suggested Haile had bipolar disorder, a mental health condition characterized by intense shifts in mood and energy. Diagnoses of bipolar disorder in children and teens have increased 40-fold over the last decade, although experts aren't sure why. Because the condition tends to emerge in adolescence, more than half of all cases are diagnosed between the ages of 15 to 25.

In Haile's case, heredity may play a role — Tiffany was diagnosed with bipolar disorder herself at age 21. She also suffers from severe anxiety. Dealing with both "can be a daily struggle," she says. "I didn't want Haile to carry that burden."

Not even yet a teenager, Haile started a regimen of mood stabilizers and non-stimulant ADHD medicines, and finally, her moods began to level out. But even with prescriptive help, her mental illness took a toll on their family.

More From The Stir: Violent Temper Tantrums May Indicate Mental Health Problems

Tiffany, her husband, Ryan, and Eviee all made changes to accommodate Haile. "She controlled everything, from what activities she did to what we ate," admits Tiffany. "We were so afraid of her outbursts that if Haile didn't want to do something, we most likely wouldn't do it."

They started weekly family therapy. In addition, Haile had weekly individual therapy sessions, monthly appointments with a psychologist to check her medications, and daily check-ins with a school counselor. Tiffany put a full-time job on hold so she could better help both Haile and Eviee. The pressure wore away at Tiffany and Ryan's marriage, too; several times over the years, they separated.

"When you're living in constant chaos with yelling and fighting and fits of rage, it takes its toll on you," Tiffany says.

More From The Stir: 6-Year-Old With Schizophrenia Can't Be as Hopeless as It Sounds

Around 2013, thanks to Tiffany and Ryan's support and a great treatment team of therapists, Haile's mood swings finally lessened. "We knew things would never be 'normal' within our home; however, we felt we'd gotten to a place where things felt 'normal' to us," says Tiffany.

Unfortunately, relapses are common in people suffering from bipolar disorder.

When Haile was 10, her violent behavior and depression returned with a vengeance. She began scratching herself to the point of drawing blood, forcing herself to vomit, and hitting herself with objects. She talked about killing herself and lashed out at Tiffany, Eviee, and even her grandparents.

When Tiffany was forced to call the police one day last winter, "I realized I no longer had any control of her. I couldn't stop her from hurting herself or others. I couldn't take away the constant hate she had for herself," she says. "I felt hopeless and helpless."

After consulting with a therapist, Tiffany agreed to admit Haile into a residential treatment center. It's more common than you'd think for young children with acute mental disorders, such as bipolar. Since 1996, short-term psychiatric hospitalization rates for kids between the ages of 5 and 12 have actually risen.

But even though Tiffany knew she was doing the right thing and felt confident in the small, personable facility for children that they chose, "it was the hardest decision I've ever had to make in my life," she says.

After admitting Haile last February, Tiffany cried for the rest of the day. And although Haile seemed more curious than scared about her new "home," the next day, when Tiffany visited for family therapy, Haile flew into a violent rage and had to be restrained. Although the staff assured Tiffany that Haile's behavior was common, "I never felt so wrong about something in my life," she says. "It killed me to leave her."

At first, Tiffany was only able to see her daughter for hour-long visits and weekly family therapy. But she could tell that being at the treatment center, with its round-the-clock staff of therapists, was helping Haile, whose diagnosis was changed to an unspecified anxiety disorder and complex ADHD with borderline personality traits. (She may still be bipolar, but since its onset is typically in adolescence, doctors are waiting to make an official diagnosis.)

"For the first time, Haile was pushed to talk about her feelings, held accountable for her behaviors, and was able to see other kids going through struggles," says Tiffany. Two medications have also helped.

Eviee, however, has struggled at home. "She didn't know what to do with her sister gone," Tiffany says. "They are the best of friends."

For a while, Eviee became reluctant to leave Tiffany's side. "Just getting her to school started to become a victory," says Tiffany.

Haile's first off-campus visit was last Thanksgiving, and her first overnight on Christmas Eve. Both went well enough that Tiffany told her daughter's therapists that she wanted to work toward bringing Haile home for good.

They agreed. Now, nearly a year after Haile was admitted, her discharge date is on the horizon.

"Haile still struggles with depression, but she's shown that she can use her coping skills to get through difficult situations and feelings that she has," Tiffany says.

The entire family is excited to have Haile home, although Tiffany does worry how her daughter will do once she leaves the highly structured environment of the treatment center.

Still, she feels she and Ryan have learned new, better ways to deal with Haile, as well as with each other. "I truly believe our family is going to be okay, and that's something I haven't been able to say for a long time," she says.

To other parents who might have a child with mental illness: "You are not alone in this," Tiffany says. "Please, please reach out and ask for help."

She's found support in private Facebook communities for parents dealing with similar issues and recommends The Child Mind Institute for information on specific conditions. Because parenting a mentally ill child can take a serious emotional toll, "take time to revamp — take a bath, go for a walk, see your own therapist," says Tiffany. "It's extremely hard to do, but if you're not okay, you won't be able to take care of anyone else."

It's taken years for Tiffany to let go of the guilt that Haile's mental illness was somehow her fault. "At times, I still worry, 'Where did I go wrong?'" she admits. "But it's gotten better … I'm truly blessed to have the family I have. They are everything to me and perfect in my eyes."

Do you know a child with mental illness? How have their parents coped?

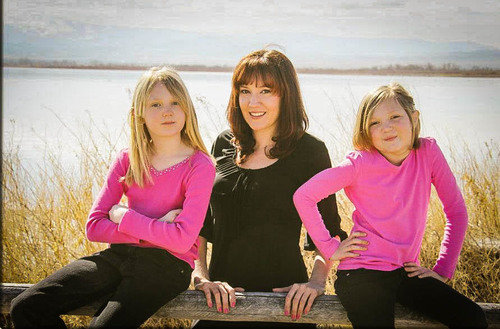

Images courtesy of Tiffany Nettleton