Our new monthly column MOM WITH aims to redefine what it means to be a "normal" mother by focusing on how it feels to live with a mental disorder. We see you, we hear you, and we're in this together.

Being a mother comes with its own set of challenges. And for some, there are more challenges to face than others. Danielle Sullivan, a neurodiversity life coach, is mom to a 6-year-old daughter with ADHD and an 8-year-old son with autism. Danielle also has depression, anxiety, and autism, which is not defined as a mental illness, but rather a neurodevelopmental condition.

Not being diagnosed with these issues until later in life made growing up as a young child difficult for Danielle, though she only realizes that now, looking back.

“Having depression, anxiety, and being autistic affected me deeply as a young child, but I only understand that retrospectively," she says. "None of my issues were identified until I transitioned out of college and began to live independently. In my first year living on my own, I struggled to work the traditional 40 hours a week without burning out. I couldn’t make or keep friends. I often forgot to eat. I was lethargic and unmotivated. I knew I was unhappy, but I didn’t understand what was wrong.”

Like any mother, Danielle had good days and bad days but felt she struggled more than others and chalked up her issues to be nothing more than a lack of motivation or ambition. She figured she was just lazy.

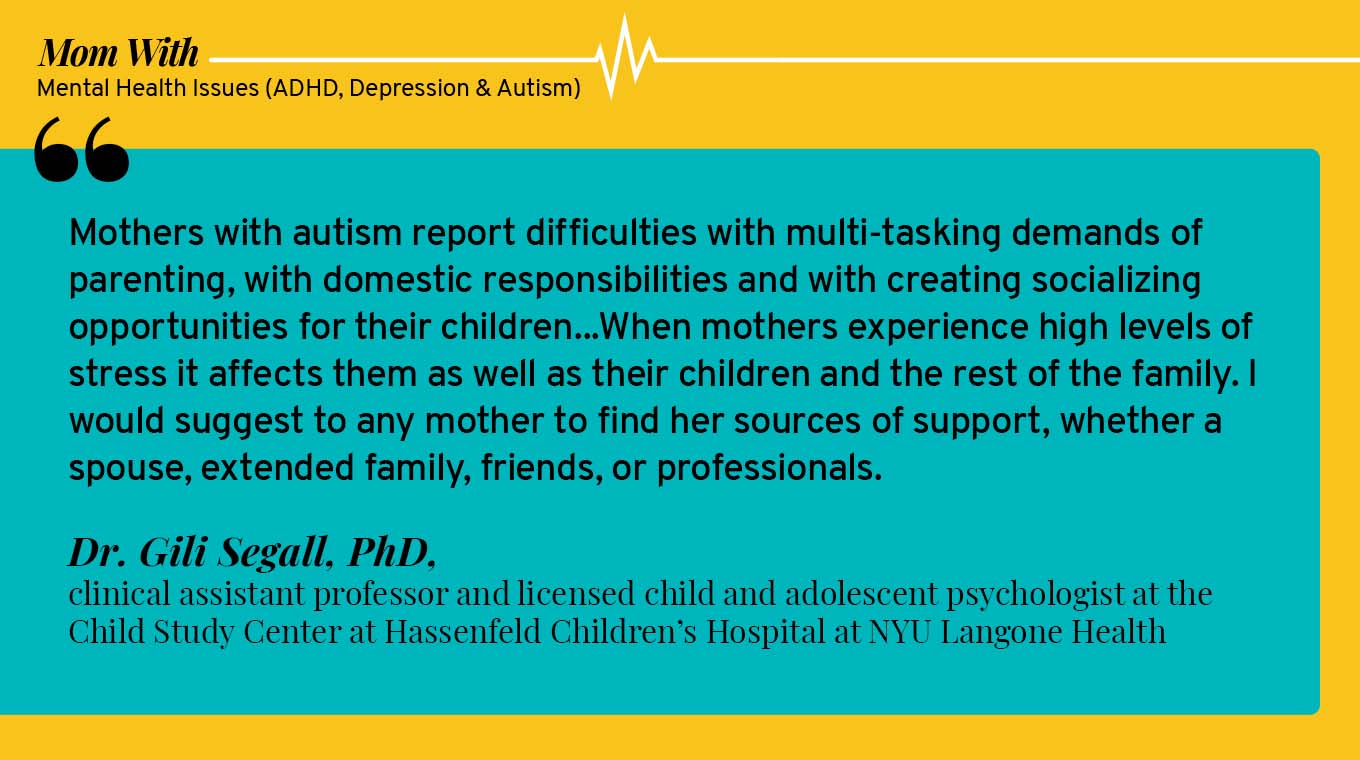

“There are definitely aspects of parenthood that mothers with autism report as more difficult than neurotypical mothers,” says Dr. Gili Segall, PhD, clinical assistant professor and licensed child and adolescent psychologist at the Child Study Center at Hassenfeld Children’s Hospital at NYU Langone Health. “Mothers with autism report difficulties with multi-tasking demands of parenting, with domestic responsibilities and with creating socializing opportunities for their children. Mothers with autism were also more likely to find motherhood an isolating experience. Difficulties with sensory experiences (such as breastfeeding), may affect them and make it harder.”

Danielle felt burned out up until she welcomed her second child at 30 years old.

It was then that she realized she felt the combination of depression and anxiety symptoms, as well as general exhaustion from autism. “My daughter was a high-needs baby, and in the first weeks after she was born, my first child, my son, was struggling with significant medical issues, eventually resulting in short-term hearing loss and an autism diagnosis.”

Danielle and her co-parent were not sleeping and were having trouble meeting their son’s newly identified needs and their daughter’s high-needs temperament. At this point, Danielle was a stay-at-home parent and was so focused on researching autism, sourcing therapy for her son and meeting her daughter’s needs, that she soon stopped taking the time to care for herself.

Segall says it is strongly recommended that mothers with autism take some time for themselves and take care of their own needs, even when it seems like their children’s needs are more urgent.

“When mothers experience high levels of stress it affects them as well as their children and the rest of the family," explains Segall. "I would suggest to any mother to find her sources of support, whether a spouse, extended family, friends, or professionals.

"Mothers with autism report more difficulties communicating with professionals working with their child, and the feeling that their parenting is being judged by others, so it would be most important to find trusted people with whom the mother feels most comfortable, to allow her the support she requires.”

When Danielle’s daughter turned 6 months old, Danielle realized her issues were intensifying and came to the decision to seek more help.

Her temper was getting shorter, and she was spending most evenings, after her co-parent got home, hiding in her bedroom. She felt over-touched and extra sensitive to noise and light. As she was so focused on researching autism to help her son, she soon came to the realization that she had autism as well. Danielle is one of many women her age who were not identified as children. This opened her eyes to why she had been struggling her entire adult life.

“As soon as my daughter could be weaned during the day (around 13 months old), I enrolled her in part-time day care, found a therapist, some support groups, and made an appointment with a new primary care doctor," says Danielle. "I was diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder and depression, to no one’s surprise.”

Investing in therapy was the right decision for Danielle and she stands by her choice.

She made a point to attend therapy every week, sometimes twice, and found it made a big difference. She is now better able to identify her emotions and evaluate whether feelings of doom and gloom are “reasonable” responses to a situation, or whether they just mean she should take a nap or eat something.

Anyone who struggles with depression and anxiety can understand how they affect your performance as a mother, and autistic individuals are at an increased risk of mental health difficulties compared to neurotypical individuals.

“A recent comparative study reported that mothers with autism were more likely to experience additional psychiatric conditions, such as pre- or post-partum depression, and reported greater anxiety compared to mothers without autism,” says Segall.

For Danielle, it was clear that when untreated, her symptoms negatively affected her parenting.

Now that she has more support and treatment, she feels her challenges make her a better mother.

“I’m more empathetic and aware of my kids’ and co-parent’s mental health," says Danielle. "All the skills I learned in therapy, like self-awareness, emotional regulation strategies, and noticing triggers ahead of time, are hugely beneficial to my parenting and make me a more connected and in-tune mother.”

Segall says her best advice to parents with autism is to spend meaningful and enjoyable time with their child when they can.

“During this precious time together, it’s always great to be mindful of sharing feelings with each other, expressing our love and appreciation to each other, and encouraging and comforting our children when they experience difficulties," Segall adds. "Validating the way they feel and problem solving together could be a great way to collaborative and make the parent-child relationship stronger.”

Danielle finds ways to talk with her children about her disorders, without ever actually mentioning medical terms.

They keep the discussion open in their house about how everybody has different brains, and sometimes their brains can get confused or overwhelmed and how important it is to take a break and breathe to get them back on track.

“We also talk a lot about how our brains are trying their best to help us, but they’re not always perfect and sometimes they make mistakes, like when we forget things or have trouble focusing, so we need to give ourselves and each other grace and just try our best,” explains Danielle.

Danielle has a very positive way of looking at her struggles and feels that her disorder does define her and is not all there is to her. Many people who struggle with some sort of mental or neurodevelopmental disorder do not want it to define them. But the truth is, our struggles, our wins, our failures, all our good and bad are what define us, even if they're just a part of us. Those things may not be all of who we are, but they make us who/what we are and that is something to own.

“I’m always going to be prone to anxiety and depression," says Danielle. "Ignoring it made it worse and harmed me for years. I’m still unearthing self-talk and behaviors that cause harm, that need to be understood, unlearned, and replaced, from years of being unidentified. Don’t ignore your struggles — integrate them into your life. Listen to them and learn from them. Find other people like you online, in support groups, through therapy. You’re not alone. We are all here with you.”