Donald Trump is making good on one of his campaign promises. As he vowed on the campaign trail, Trump is considering an executive order that would limit immigration from Muslim countries, including Iran, Sudan, Syria, Libya, Somalia, Iraq, and Yemen.

His "Protecting the Nation from Terrorist Attacks by Foreign Nationals" executive order would also halt all refugee admissions for three months and prioritize admitting "religious minorities," which likely means Christians, according to Vince Warren, executive director of the Center for Constitutional Rights.

As many critics of the proposed "Muslim ban" noted, barring refugees based on religion, ethnicity, or any other marker of identity is ineffective and detrimental.

"By privileging Christians we are cementing the notion that the government action is based purely on religion," Warren told Slate. "It's hard to dress this all up as a purely country-based ban, when you are separating one religion against another within the same country."

The "Muslim ban" also recalls another stain on America's history: Japanese internment.

After 2,000 Americans died in an attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, president Franklin D. Roosevelt instituted executive order 9066.

The executive order allowed the War Relocation Authority to forcibly move over 100,000 Japanese Americans to internment camps.

Japanese-Americans had to register and relocate to "assembly centers," according to The Los Angeles Times.

Japanese-Americans were crammed into camps in Arizona, Utah, California, Wyoming, Arkansas, Idaho, and Colorado from 1942 to 1944, according to the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

The Los Angeles Times notes that two-thirds of those funneled into camps were American-born citizens.

The American government argued that national security relied on the imprisonment of Japanese-Americans. Military officials, like lieutenant general John L. Dewitt, argued that internment was a necessity.

In 1942, 23-year-old Fred T. Korematsu refused to leave his home in San Leandro, California for an internment camp. He appealed a conviction for violating the executive order to the Supreme Court — and he lost.

Dewitt submitted a report to the Supreme Court in favor of the government. In that report, he wrote that "a Jap's a Jap. It makes no difference whether he is an American citizen or not."

The justices agreed. In the affirmative ruling, justice Hugo Black argued that certain situations justified the imprisonment of Americans based on their ethnicity.

"Pressing public necessity may sometimes justify the existence of such restrictions; racial antagonism never can," justice Hugo Black wrote.

In 1944, Roosevelt rescinded the executive order, according to The Atlantic. Japanese-Americans were then allowed to leave the camps and return to their former homes.

The last camp closed in 1946, but internment is a permanent stain on America's history.

America has attempted to make amends for violating humanity. In 1984, federal district court judge Marilyn Hall Patel overturned Korematsu's conviction.

"In times of international hostility and antagonism, our institutions, legislative, executive and judicial, must be prepared to exercise their authority to protect all citizens from the petty fears and prejudices that are so easily aroused," she wrote in her decision.

President Ronald Reagan also signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 into law.

Each Japanese-American camp survivor earned $20,000 in reparations. Overall, survivors were awarded more than $1.6 billion.

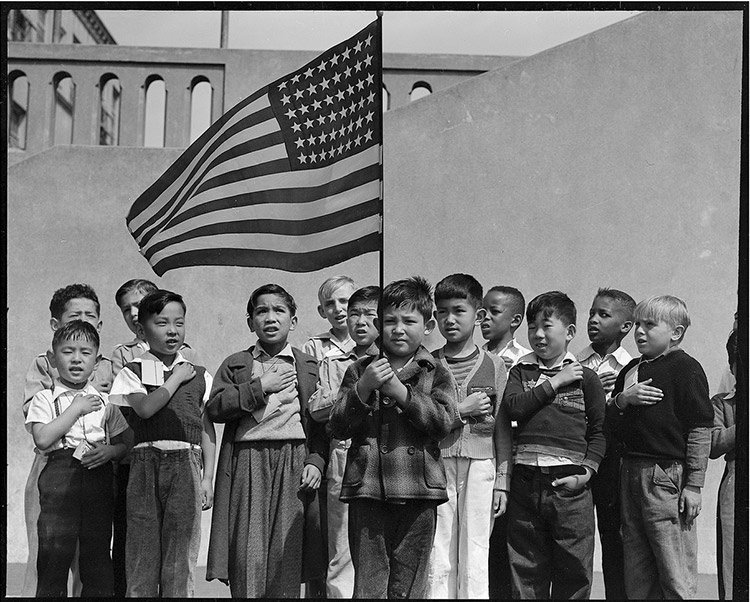

Yet, Dorothea Lange's photos of Japanese internment camps remained hidden for 60 years.

The US government hired Lange in 1942 to document Americans through photos. She began photographing Japanese-Americans in internment camps soon after.

She opposed internment, so her unflinching photos captured the true toll imprisonment took on Japanese-American families.

In 2006, more than 800 of her sobering photos were unearthed and released.

They were also compiled into the book, "Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment."

Her photos are a reminder of what's at stake when politicians, like Trump, propose the targeting of Americans based on their identity.

Japanese internment didn't happen that long ago. Learning from that history will, hopefully, prevent the US from repeating it.