For many women (myself included), getting an epidural felt like a no-brainer: Why suffer the pains of labor if you don't have to? Michelle Babcock thought so too, which is why this 33-year-old in Los Angeles went through with the procedure in 2012 while giving birth to her son. Yet complications from her epidural have been haunting her ever since.

Many moms think of epidurals as a godsend but have only a vague notion of the risks. What was your view of epidurals before you got one?

In my birthing class, it was spoken of almost as if it were a modern marvel; women no longer need to endure the inhumane suffering of childbirth thanks to advances in modern medicine. It was almost like, "Why wouldn't you get the epidural?"

At the hospital, prior to getting induced, the nurse overseeing my induction gave me the informed consent form for the epidural. After reading through the form, I asked the nurse what "nerve damage" meant. She said that, for example, a nerve could be nicked and that I might feel a numb spot on my leg for awhile. She went on to say that, if that happens, it should go away on its own in time … that she didn't understand why women choose to suffer for so long without an epidural, only to be too tired to push and end up with a C-section. She recommended one to me "just in case I needed a C-section." During labor, the anesthesiologist told me that of the 6,000+ epidurals he had administered, only two had adverse reactions, which were spinal headaches that were easily fixed.

So how did your epidural go? How soon did you sense something was wrong?

Upon administering the epidural needle, I immediately felt pain on my left side. The anesthesiologist either reinserted the needle or adjusted it somehow. My blood pressure plummeted, and I almost passed out. I was given IV medication and oxygen to keep from fainting. I could not feel anything from the chest down until after delivery when the medication was cut.

After delivery, when the nurses asked me to stand up, I could barely stand or walk because my legs were so weak. They continued to be weak, like jelly, for my entire hospital stay, from Friday to Sunday afternoon, and my feet had intermittent numbness. I had terrible pulsating lower back pain every time I sat down, and headaches were common.

What symptoms did you experience after you went home?

Two days later, I felt pins and needles in my legs, and my arms started going numb, so I freaked out and we went to the ER twice that week with symptoms getting worse. This continued for months, along with uncontrollable muscle spasms and bizarre neuropathic sensations, like water running down my leg or worms crawling underneath my skin.

It had a huge impact on my life. I used to be a very physically active person. Before my injury, I was an assistant cross-country coach and ran miles every day. In the months after having my epidural, I could barely walk around the block. I depended on others to help me take care of my baby, as I had trouble bending over, picking him up, and holding him for long periods of time. I was an emotional wreck, especially during the first six months, because all of the doctors were writing me off as a crazy postpartum anxiety case. My family didn't know how what to do or whom to believe because the doctors were basically telling them that it was all in my head. I desperately wanted to know what was wrong with me so that I knew what I was facing and could get proper treatment, and so that others close to me could understand and lend their support.

Eventually you were diagnosed with adhesive arachnoiditis, an inflammatory condition affecting a layer of membrane surrounding the spinal cord. How did it feel to finally have an answer?

When I was finally diagnosed, it was both a shock and a relief. Since my diagnosis, I have undergone several treatments for my pain. I see a pain management specialist and osteopath who have been able to help keep my pain levels moderately low and my other symptoms at bay, so I am able to do much more than I could in the early months of my injury. However, I still live with many limitations. I have to be careful with how I move so that the wrong movement does not send me into a flare, which may spike my pain level for days. I cannot sit or stand in one position for long periods of time. Plane and car rides are torturous. I have to lie down every few hours to ward off symptoms that arise due to a disruption in my cerebrospinal fluid flow.

Emotionally, I have gone through many stages of grief. I had to take time to grieve and bury my old self, and make peace with the fact that I will never be who I was before my injury. I have finally come to terms with the fact that I am no longer an active runner whose daily activities are limitless. I am a person living with a chronic illness who oftentimes has to live by the spoon theory — how many spoons do I have left today, and what activity is worth using one of my precious spoons for?

How do you cope with all this while juggling the responsibilities of motherhood?

I look and act normal on the outside, so it is often difficult for others to understand or even know that I have a spinal disorder unless my pain is not being controlled that day, in which case I may walk funny or have to lie down. I have to think twice before accepting a friend's invitation. How will I feel that day? Does it involve any activity that may send me into a flare, like too much sitting or walking?

In the beginning, it was difficult for me to relate to other mothers. I used to fantasize about what it would be like to be a healthy mom with zero limitations, and I was envious of other moms, many of whom made the same choice that I made about getting an epidural, only with no consequences. Not that I would wish this on anyone; I just couldn't wrap my mind around the fact that the same decision could have two polar outcomes, one benign and the other life changing. I would hear of other moms' "problems," how to get rid of their babies' hiccups, and wish I had those problems. It was difficult for me to go to a park with my son because I felt like a fish out of water. I would see other moms playing soccer or on the monkey bars with their kids, and I would get upset that I couldn't do those things with my own son.

I have since learned to change my perspective and now, most of the time, focus on a glass-half-full mentality. I feel lucky that I am not paralyzed, and that I can walk and get out of the house. I frequently remind myself not to make assumptions about others or compare myself to them; that they have their own crosses to bear, physically or otherwise. Who's to say that they don't have an invisible illness themselves?

What do you want other women to know about epidurals?

I want other women to know the truth about the risks of an epidural. Many medical professionals minimize these risks because epidurals are lucrative procedures. They line the pockets of anesthesiologists and hospitals, and they make the doctor's job easier in that they don't have to deal with a high-maintenance woman in true labor. Also, OBs can be as rough as they need to be "down there," and nurses don't need to spend so much energy coaching you through a natural labor.

I want women to be given adequate informed consent, and I want "adhesive arachnoiditis" and an explanation of what it is listed on informed consent forms. To this day, women are not giving their true informed consent before these procedures because they are not told about this risk, or they are told that it is so rare it is not worth mentioning. I want women to know that this disease is not as rare as many medical professionals would have us believe.

More from The Stir: Everything You've Ever Wanted to Know About Epidurals But Were Afraid to Ask

After my diagnosis, I learned of thousands of others who have this disease from botched spinal procedures. It took many of them years to get an honest diagnosis, and the majority of these cases remain unreported, as there exists no reliable method of reporting or monitoring its occurrence. Many arachnoiditis patients were told they had other neurological disorders like fibromyalgia or "failed back surgery syndrome." Really? They are just swept under the rug by the medical community, as it is not in its best interest to disclose a disease that may hurt a profitable industry and that, nowadays, is caused by a doctor's medical error.

What have you learned from this experience?

I have learned many lessons as a result of this disease. The first one is to trust my gut. Had I trusted my gut and refused both my induction and epidural, I believe I would still be healthy today. I put too much trust in my physicians and did not listen to my own body. Living with this disease has also taught me what is really important in life.

It has really put things in perspective for me. I appreciate the little things in life so much more than I did before my injury. A cup of tea. My son's smile. My husband's laugh. I don't care if I have a jiggly postpartum belly, I don't care about the numbers on the scale or if people see me without makeup. I don't care if the house is a mess or if the dishes aren't immediately loaded into the dishwasher. These are things I actually cared about pre-arach because I didn't have more important things to worry about. I also have learned compassion, especially for those worse off than me. It took something drastic to teach me how to live a more meaningful life and be a better person, with limitations and pain, yes, but living meaningfully nonetheless with a husband and son whom I adore.

Did you know the risks of an epidural before you got one? Would you get one after reading this mom's story?

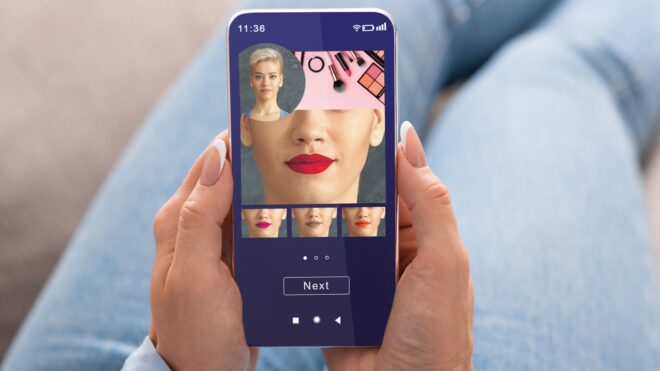

Image via Michelle Babcock